Tuesday, 24 November 2009

Monday, 16 November 2009

The Everyday in Art

The presence in contemporary art of everyday, domestic objects such as a bed is now a commonplace of contemporary art, even if contemporary critics rarely ask whose everyday domesticity might be re/presented. Many of life's key experiences and rites of passage — being born, sleeping, dreaming, having sex, giving birth, and dying — happen in bed.

Rachel Whiteread made numerous bed pieces which she placed on the floor, inviting yet denying rest, cots by Permindar Kaur or Mona Hatoum, Richard Hamilton's brutal Treatment Room of 1984 (Arts Council Collection, London, recently exhibited in Protest and Survive at the Whitechapel Art Gallery) or Bill Viola's Science of the Heart of 1983 (shown in Spectacular Bodies at the Hayward Gallery) play on, prey on, the oscillations between life and death, the body's presence and absence. None have the comforts usually associated with the bed in consumer culture of the 1980s and 1990s with its boom in home decoration and plethora of styles from the minimalist to the ornate. One of Sarah Lucas's most complex pieces about sexuality and sexual difference is Au Naturel of 1994 in which a sagging, stained mattress is propped up against a wall. Impossible to sleep or rest upon, its surface is interrupted the objects placed upon it: a bucket, melons and a cucumber. So long a stage for the performance of the female nude, upturned the mattress becomes the site for the play of fantasies and cultural representations as the artist's trades with her audiences the crude sexual stereotypes in circulation in contemporary culture.

Tuesday, 20 October 2009

A Country Refuge

The project was a collaboration born of a conversation about the mutual feelings of exposure and vulnerability Kirsten and I felt whilst on a drawing assignment to the rocky headland on the south coast of Skye a few weeks ago.

On facing the elements, unprotected and alone, we felt an overwhelming desire to find shelter, warmth and protection, and as there was none available, we decided to build our own safe haven, using the only materials we had available, those which existed naturally on the Island; branches, twigs, grass and rocks.

This work stems from a common interest in the theme of human vulnerability and the desire to protect, encase and self-preserve that comes instinctively to us. The built environment exists to give people places in which they can find shelter, thus in the natural environment we must, like animals, find a way to create shelter for ourselves.

Sadly we ran out of time so the shelter remains unfinished, however, for me, it has taken on a new character as a drawing in space, a natural curiosity that I hope future passers by will take a moment to ponder upon. Had the shelter been completed, our idea was that in it's very making, it would be unmade, the structure flowing from the lines of the rockface becoming an extension of the natural environment from which it arose from.

Not a word was spoke between us, there was little risk involved

Everything up to that point had been left unresolved.

Try imagining a place where it's always safe and warm.

"Come in," she said,

"I'll give you shelter from the storm."

Thank you Bob Dylan

Wednesday, 23 September 2009

Tuesday, 16 June 2009

Sunday Afternoon in the Queen of Parks

Following all that heavy stuff about the economy and our world in crisis I thought it prudent to remember that some things are free, nature is beautiful, and for the paltry cost of a pencil and a piece of paper, a lovely afternoon can be spent, close to idle, whiling away the day drawing in the park.

Wednesday, 13 May 2009

A Felt Covered Solution for a New Crisis

Joseph Beuys, Infiltration homogen für Konzertflügel (Infiltration Homogen for Grand Piano), 1966

Beuys died three years before the reunification of

Because Beuys is a German artist, it is impossible not to see the wounds of history everywhere, with a surpassing melancholy that dwarfs his attempts to commit his sculpture to an optimistic democratic politics. Beuys hoped his lumps of fat spoke of fluidity and progressive change. In fact, they are blocks of rancid yellow memory - fat from

The first Beuys I ever saw was at the Georges Pompidou Centre: a grand piano smothered in grey felt, with a red cross sewn on it. It struck me as tragic, and it still does. The piano is German culture, the heritage of Beethoven, sealed now inside felt, with an ambulance sign - damaged, wounded, recuperating. It is the sculptural equivalent of the sanatorium in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain.

When I tried to find out more about Beuys, I was baffled. The felt swaddling the piano, according to Beuys, was meant to heal it, to save it. Yet this efficacious magic doesn't actually form part of the piano's aesthetic impact. There is no sense of redemption - just of sickness. Now I realise it doesn't matter what Beuys said; probably at some level he knew he was whistling in the dark when he claimed his art was upbeat and spiritually transfiguring, when really it is shockingly lumpen, and macabre.

Tuesday, 5 May 2009

Thursday, 23 April 2009

Simon Starling - Three White Desks - Tate Triennial - Altermodern

This work by Simon Starling (Three White Desks) was created by sending 3 cabinet makers in 3 different countries photographs of a desk once owned by Francis Bacon. Starling requested that each cabinet maker recreate the desk as closesly as they could to the likeness in the photograph accompanying his instructions, no dimensions or further information was sent enclosed. Starling sent the instructions to each craftsman in turn.

This work by Simon Starling (Three White Desks) was created by sending 3 cabinet makers in 3 different countries photographs of a desk once owned by Francis Bacon. Starling requested that each cabinet maker recreate the desk as closesly as they could to the likeness in the photograph accompanying his instructions, no dimensions or further information was sent enclosed. Starling sent the instructions to each craftsman in turn.When the first desk arrived, Starling photographed it and sent the image off to the second cabinet maker and so on, until in a Chinese Whispers style way, the likeness of the desks degraded, through the effects of transit, digital communication and distance.

This work makes me think of the way families and friends move or are diaplaced throughout countries and continents and are therefore forced to communicate in a second hand way, the ever decreasing quality of the desks serving as a metaphor for the weakening of the social structures and communities in which individuals find strength and inspiration.

The Sleepers on the Track Have Woken Up

‘Why do cats understand what you say?’ ‘Where does hair go when you go bald?’ ‘How can the city control illegal bicycle parking?’ These are just some of the questions that Marcus Coates has attempted to answer by descending into the ‘lower world’ and consulting the birds and animals that he encounters there. Usually they respond in cryptic clues; uncharacteristic behaviour is what he is looking out for, which he then does his best to interpret for his audience on his return.

Coates was inducted into the ancient techniques of shamanism on a weekend course in Notting Hill, London. The workshop trained participants to access a ‘non-ordinary’ psychic dimension with the aid of chanting, ‘ethnic’ drumming and dream-catchers. Coates has explained the process as essentially being a form of imaginative visualization. Historically the shaman would have been employed to solve the daily problems of the community; since these usually involved the finding and killing of animals, shamans were valued for their ability to communicate with other species in the spirit world. Shamanism’s contemporary abstracted form in the West still relies on animals as ‘guides’, but it encourages practitioners to project personal spirit worlds in terms that are familiar to them. During his trance the man sitting next to Coates met and talked to a gerbil.

Coates himself is a keen ornithologist and naturalist; the animals that he encounters in the ‘lower world’ are usually from areas of British landscape that he knows intimately. Much of his past work has reflected his sense of alienation from such places, a frustration that manifests itself in the sentimental yearning to ‘get back to nature’. Indigenous British Mammals (2000) was Coates’ ludicrous attempt to reverse the flow of anthropomorphism and subsume himself within the fabric of the natural world, emulating wild animal calls while buried under the turf of deserted moorland; in Goshawk (1999) he persuaded foresters to fasten him to the upper branches of a Scots pine so he could see the world through the eyes of a hawk scanning for prey. While the humour of these works springs from the naivety of the desires they embody, by subjecting himself to such vivid, visceral experiences Coates holds on to the possibility of personal transformation and so restrains them from snide satire.

The ambiguity of Coates’ own investment in the processes he embarks on creates a constant itch in the understanding of his position; who is laughing, and whom exactly are they laughing at? This question was at the forefront of his first shaman work, Journey to the Lower World (2004), in which he filmed himself performing a shamanic ritual in the front room of a Liverpool tower block that was scheduled for demolition. The audience of bemused residents fought to suppress their giggles as Coates, dressed in the skin of a red deer, began by vacuuming and spitting water onto the carpet, then emitting feral whistles, grunts and barks as he entered the ‘lower world’.

Despite his audience’s obvious scepticism (of both shamanism and of the contemporary art world), the question they asked Coates about the lower world was sincere and unguarded: ‘Do we have a protector for this site? What is it?’ He had gained their trust and implicated himself in an intimate system of exchange. His tentative answer, interpreting peculiar feather patterns on a sparrowhawk’s wing as being indicative of the community’s need to ‘stick together’, acknowledged this responsibility. While remaining deeply uneasy about the employment of artists in the public sphere as ‘problem solvers’, Coates has said that often the most valuable thing that comes out of such performances is the audience’s sense that they are being listened to. This in turn prompts them to begin talking objectively about issues that concern them, even if, as in the case of Mouth of God (2006), it is to a man with a stuffed hare strapped to his head.

This is Coates’ best trick; despite looming large in the production of his works, he somehow manages to usher people towards a revelation of sorts within themselves. He achieves this again in his work Dawn Chorus (2007), the most recent and accomplished of an ongoing series of works in which he teaches people how to mimic birdsong by copying slowed-down recordings of birds, filming them and then speeding up the footage to avian pitch again. The multi-screen video installation shows 19 people caught alone in quiet moments, intermittently breaking into birdsong. While the ornithologist in Coates clearly relished the challenge of reproducing the sequence and positions of a dawn chorus in the gallery, the real magic lies in the videos’ knack of not only creating highly convincing birdsong but also accelerating human movements into the nervy fidgeting of birds.

The melancholy of Dawn Chorus is born of the solitary figures’ isolation, not only from the world of the birds and the beasts but also from each other. Deceptively, Coates’ real subjects are not the outdoors and the unknown but interiority and introspection. This is the true locus of ‘nature’ in the modern world, he seems to imply; not in the open spaces of the countryside, so obscured by cultural projection and anthropomorphism, but in the withered memory of something wild and ancient, buried deep within ourselves.

Insects, Insects, Insects

As surveillance?

I went along to the CCA yesterday to see the Edwyn Collins show, it completely renewed my enthusiasm for drawing from nature. So, I've been left thinking about how to incorporate the natural world into this project... the institution as metaphor for our increasingly controlled society, ooh that sounds a bit serious.

Rabbits lurking in corners in our yet un- CCTV'd countryside, birds with camera's, capturing the movements of rebellious sheep. I hear dissent is brewing up north, it's time to act....

Wednesday, 25 March 2009

The Institution as Metaphor

Some key themes I am interested in -

- Dualism (the body as a machine/the idea of the essence/ephemeral nature)

- Identity

- Social Control/Obedience to Authority

- Reward

- Individual liberty

- Psychoanalysis

- Self presentation

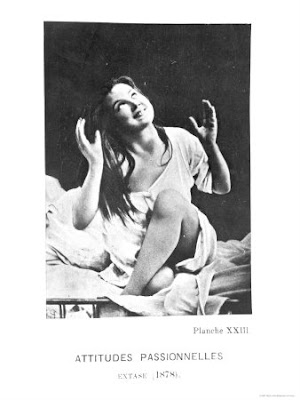

During the course of the last project I became interested in looking at the unconscious, particularly the idea of the idea of ’woman’ and the unconscious. I took a particular interest in the Iconographie Photographique de La Salpetriere as the work embodies many of the themes which I became interested in exploring.

The Iconographie Photographique de La Salpetriere is a visual record of various states of hysteria recorded at the Salpetriere Clinic in

The experiments at the Salpertiere are also of interest to me as the women depicted in the photographic records appeared to be obedient and compliant to the demands of the doctors. I am interested in why they freely ‘performed’ for the camera. It could be because they longed to be in favour of those in power or simply because they had been taken from the real world and placed in an institution where this mode of behaviour became the norm.

I am interested in why, in the real world, people chose to perform/conform ‘freely, outwith the confines of the institution. Acceptance of the expected modes of behaviour is a condition perpetrated by the society we live in; few people express any interest in acting to change the status quo or can see how they can remove themselves from the confines of a mundane/non-questioning existence.

Following from this I intend to use the institution as a metaphor to investigate areas such as social control, individual liberty and the perception of the self as thinking and acting being.

Friday, 20 February 2009

Charming Augustine

The film is inspired by series of photographs and texts on hysteria published by the great insane asylum in Paris in the 1880's under the title of the Iconographie photographique de la Salpetriere. It is an experimental narrative based on the case of a young patient, Augustine. At fifteen she was admitted to the hospital suffering from hysterical paralysis. The doctors were captivated by her frequent hysterical attacks. They appeared extraordinarily theatrical and photogenic. She became the star, the "Sarah Bernhardt" of the asylum. Yet at the same she was deeply disturbed. She had visions and heard voices. She hallucinated.

The film explores connections between attempts to document her mental states and the prehistory of narrative film. The role of the motion studies by Marey and Muybridge in the birth of cinema is well known. However while they attempted to study the mechanics of the body, the doctors at the Salpetriere, working with similar cameras, aimed to unlock the secrets of their patient's minds.

The film attempts to show how patients like Augustine supplied the psychic drive that would come to flower in the works of D.W. Griffith. Thus the language of the film changes; at first it is simply a medical document, then it becomes is an indication of Augustine's interior perception, her hallucinations. Finally she becomes "disenchanted" both in the contemporary sense of that word and in its original meaning of being awakened from a magnetic sleep or hypnotic trance.

Tuesday, 17 February 2009

Shattering the Hard Shell of Certainty

Today... I have been having a look at the Museum of Jurassic Technology in LA. This curious museum first first came to my attention when I watched a documentary about the German filmaker, Werner Herzog. During the course of an interview, Herzog took the interviewer there and introduced it as his favorite place in all of Los Angeles.

The museum's name is a puzzle as the Jurrasic period ended 150 million years before humans made an appearance on this earth... however, that's beside the point and the museum houses a most fascinating collection of items and curiosities.

Here are a few of the permanent collections on display-

- A collection of decomposing antique dice once owned by magician Ricky Jay and documented in his book Dice: Deception, Fate, and Rotten Luck

- A collection of micro-miniature sculptures and paintings, such as a sculpture of Pope John Paul II carved from a single human hair and placed within the eye of a needle

- A collection devoted to trailer park culture, entitled "Garden of Eden On Wheels."

I've always had a bit of a thing for trailer parks so the last exhibit is of particular interest to me.

Going back to my earlier point, I first heard of this place through Herzog, and today, it came into my life again when I was searching the net for information on the Salpetriere Clinic in Paris.

The Salpetriere was a clinic where 5000 women, who were all thought to be hysterical, where incarcetaried duing th first part of the 1900's. Charcot, a pioneering/deeply disturbed doctor there, was interested in recording the physical manifestation of the illness through photography. I have found a few books covering the topic but today, excitingly, I found a film. The film is called 'Charming Augustine' and it deals with the same sort of issues, using the Salpetriere as a backdrop. The filmmaker, Zoe Beloff, is interested in the doctors attempts to record the mechanics of their patients bodies in their efforts to unlock the secrets of their minds. This is mega interesting to me. I had a look into her page and found her father to be a philosopher who wrote extensively on dualism and had a very keen interest in art. It all comes together; philosophy, hysteria, photography, trailer parks and Werner Herzog. I'm sure the Museum of Jurrasic Technology would approve of such an eclectic mix.

Tuesday, 3 February 2009

Wunderkammer

Cabinets of curiosities (also known as Wunderkammer, Cabinets of Wonder, or wonder-rooms) were encyclopedic collections of types of objects whose categorical boundaries were, in Renaissance Europe, yet to be defined. Modern science would categorize the objects included as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art (including cabinet paintings) and antiquities. "The Kunstkammer was regarded as a microcosm or theater of the world, and a memory theater. The Kunstkammer conveyed symbolically the patron's control of the world through its indoor, microscopic reproduction."[1] Of Charles I of England's collection, Peter Thomas has succinctly stated, "The Kunstkabinett itself was a form of propaganda"[2] Besides the most famous, best documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe, formed collections that were precursors to museums

Monday, 2 February 2009

Archiving the 1970's Art World - Das Schubladenmuseum

From 1970 to 1977 Distel started working on his landmark 'Museum of Drawers' (Das Schubladenmuseum)], a found cabinet with 20 drawers each containing 25 tiny rooms where he invited living artists to contribute a miniature work of art. Artists included were: Arnulf Rainer, Carolee Schneemann, Mergert Christian, Pablo Picasso, Robert Cottingham, Billy Al Bengston, Joseph Beuys, John Baldessari, Carl Andre, Chuck Close, Tom Blackwell, Tom Phillips, Joe Goode, Charles Arnoldi, Camille Billops, Nam June Paik, Frederick J. Brown, Robyn Denny, Valie Export, Mel Ramos, Edward Ruscha, Dieter Roth and John Cage. At the same time George Maciunas was working on his Fluxus "Flux Cabinet" (1975-77).

Lynn Hershman Leeson - The Secret of Eternal Youth

Artist Lynn Hershman Leeson Discovers Secret of Eternal Youth: Reynolds Wrap

5/30/08 at 3:15 PM 00Comment 00Comments

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Wrapped (2007).Courtesy bitforms gallery nyc.

You Can't Bottle it

Essence, athmosphere, ether. Buy some air from Mecca. Grass from Celtic Park. Holy Water from Lourdes. A chunk of the Berlin Wall. A bit of Mackintosh to take home - a minature chair, a necklace.... or just walk about and inhale the place.

I once went to the Louvre and it seemed that most people were more interested in taking home a photograph of the Mona Lisa than actually looking at her.

You can buy a new face in a bottle, knock off 20 years, or a new lifestyle in a sofa, it'll change everything, you'll be much thinner when you lie on it .... and your adoring husband, will, of course, be buff with chiselled cheek bones.

Wednesday, 28 January 2009

Light Comes, Light goes

Following last week's visit to the GSA archive, I've been thinking a lot about the non-archivable elements of the Mack building, the light, the atmosphere, the fleeting glances and conversations, largely passing by unnoticed, but put together creating the whole that gives the space it's atmosphere and character

Some elements are ever changing, never emerging in the same way twice. The light is one of those things, it changes subtley minute to minute and, in the passing of a few hours, can completely change the way one percieves the space. I took a trip round the stairs and back corridors, aiming to find some interesting light and explore the effect that it has on the atmosphere and in turn, probably the work that's being created too.

The Oral Tradition

Back on the subject of the non-archiveable, I have been thinking about the oral tradition of the Mackintosh building; the stories that get passed on through generations of students and staff and perhaps get lost or, in a Chinese whispers kind of way, amended as time passes.

A bit on Oral History from Wikipedia-

Oral history can be defined as the recording, preservation and interpretation of historical information, based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speaker.

It often takes the form of eye-witness evidence about past events, but can include folklore, myths, songs and stories passed down over the years by word of mouth. While it is an invaluable way of preserving the knowledge and understanding of older people, it can also involve interviewing younger generations. More recently, the use of video recording techniques has expanded the realm of oral history beyond verbal forms of communication and into the realm of gestureDid you notice anything?

Philip Glasss', Silencio and Martin Creed's Turner Prize winning, Work No. 277, The lights going on and off have in common the heightened sense of awareness they give to the listener/viewer or participant in the work. In the absence of 'something' to listen to or look at, one looks around the space they occupy in a new way or, in the case of Silencio, listens to the unpredicatable symphony of sounds that exist already.

I like this idea, the idea that there doesn't need to be anything (loosley speaking) to make something happen in the mind of the participant. Although in both cases, something does exist; the CD or the lights going on and off, there is no 'work', in traditional terms.

This project has heightened my awareness of my everyday surroundings and made me look at the place where I come to work and learn through wider and more aware eyes. I would be interested in capturing something of the essence of Creed and Glass' work in the work I produce.

Tuesday, 27 January 2009

Only Passing Through

Some artists I've been looking at for this project are Eva Hesse (a perennial favorite of mine), Christine Borland and Arte Povera sorts like Pistoletto, particularly his reflection painitings and use of mirrors. I like the idea of capturing the mirror image of the days passing in the Mack, an etheral glimpse of people going about the business of creating and making work, much in the same way as they have done in this building for the past 100 years.